The following article was written by community member Doc_H, who was kind enough to write this awesome article comparing LOTR LCG with the newer Marvel Champions and looking at some similarities and differences in the games. We’re not saying that one is better than the other, but seeing how both have had the same designers, it would be possible that if you enjoy one game, you might enjoy the other as well. Thanks, Doc_H, for writing the article!

So you are considering a relocation from Earth-616 to Middle-earth? While one of several sibling Living Card Games, keep in mind that FFG began Lord of the Rings: The Living Card game in 2011, a full eight years before Marvel Champions (which I’ll call LOTR and MC). MC is the eleventh LCG they created; LOTR was just the fourth. Their experience making several LCGs between the two definitely benefited MC in terms of elegance and polish, although LOTR remains a phenomenal game for both solo and group play. In this article, I will compare different facets of each game, showing similarities and differences.

Heroes

For starters, instead of playing a single identity, in LOTR you are allowed up to three heroes. For economic reasons, most decks use three. Later in the life of the game, situations arose that led people to play two-hero decks or even one-hero decks, but these are not how you would want to learn the game. There are no alter-ego states like for MC’s heroes. A typical hero looks like this:

The 11 is the hero’s starting Threat and is, in most cases, simply a summation of the other four values on the card (I will discuss LOTR’s concepts of Threat later, but note that this term is not the same as Threat in MC). Under Threat, the trio of black vertical numbers on the scroll (in Gimli‘s case, each is 2) represent Willpower, Attack, and Defense from top to bottom. The red 5 below them is Gimli’s starting Health value. Note the unique symbol next to Gimil’s name, a designation also used in MC. The card type (in this case, a “hero”) is always listed at the bottom. Both games place traits in bold below the hero’s name. And then you see Gimli’s specific ability (increasing his attack for damage he has taken). Finally, note the red sword pommel in the bottom left of the card, which tells us Gimli belongs to the Tactics sphere. This is a major difference between the games: LOTR heroes come with their own sphere (analogous to MC’s aspect). Only one hero exists in all four aspects, Aragorn (with his ability text being different among the four). This card, like other Tactics cards, has a reddish background with the same symbol behind his ability text.

Like MC’s aspects, there are four spheres in LOTR: Tactics (such as this Gimli), Lore (green), Leadership (purple) and Spirit (blue). As in MC, certain traits, styles, effects, and abilities cluster in one sphere more than another. Neutral cards (in gray) also exist.

When you have chosen your lineup of heroes, you have, by default, also chosen which one, two, or three spheres your deck will contain (based on those sphere(s) of the hero). Some decks only have heroes from one sphere (a “mono-sphere deck”), other decks contain heroes from three spheres (“tri-sphere”), and many decks split the difference with a pair of heroes from one sphere and a third hero from a second sphere (“dual-sphere”). Some LOTR players who have migrated to MC love Spider-Woman since she gets to choose two aspects for deck construction. Conversely, if you enjoy building decks for Spider-Woman in MC, you will probably like constructing LOTR decks.

The required two aspects for Spider-Woman give a hint of what deck-building in LOTR is like.

Resources

One of the reasons your choice in spheres matters is this: each hero generates one resource each round (a token is used as a counter), and this resource matches the sphere of the hero. Unlike MC, cards are not resources in LOTR. Furthermore, there is no hand-size limit, and you can only draw one card each round (regardless of the number of heroes you have or your current hand size). So, in our Gimli example, each round, he generates one Tactics resource, and you would add one card to your hand each round regardless of the number of heroes in play. Gimli’s Tactics resources can only be used to pay for Tactics or Neutral cards. While every player starts the game by drawing seven cards, in LOTR, cards, and resources are more valuable than in MC due to scarcity. In many games, you will see only around half of your deck.

Deck Building

Naturally, deck construction must consider the fact that you usually will not get through the deck. You are allowed to have up to three copies of a card (unless card text specifies only one per deck), and often you will want to include three copies of the strong cards or cards important to your deck’s “engine.”

Compared to MC, initial deck building and subsequent fine-tuning in LOTR take more time. And in LOTR you will be hard-pressed to port a deck build to another set of heroes since the heroes’ sphere/abilities dictate a large part of what cards comprise the deck. So, in MC, while taking a perfect protection build from Black Panther to Captain America might require very little tinkering, that is not going to work in LOTR. Since there are no kits of 15 cards bundled with each hero, what Gimli has on his hero card is all he always gets. On one hand, the heroes are restricted by being tied to spheres. The opportunity to build any MC hero in any aspect has no parallel in LOTR. On the other hand, there is great freedom being able to build a deck with the hundreds of tactics cards available (alongside the possibility of having access to one or two other spheres). Keep in mind, though, that so much freedom can be a burden. Despite the huge number of player cards, strong decks usually revolved around the relationship between a few of the cards.

The freedom to choose the entire deck also means there is a steep learning curve. Many decks will fail. Unlike X-23, Dr. Strange, or Spider-Ham, success is not guaranteed. In LOTR, winning depends primarily on the deck construction (and its subsequent piloting), not just the hero kits.

In general, decks include the three main player card types in LOTR: allies, attachments, and events.

Allies

How many similarities between these two neutral heroes available in their respective core sets can you spot?

Although appearing similar to a hero, the major difference is this character has no threat like Hero Gimli; instead, there is a cost of 2 resources to put him into play (which would be from the red Tactics sphere in this example). Unlike MC, there is no consequential damage for activating him, so in theory, he could be played in the first round and remain on the table the entire game. Also, unlike MC, there is no ally limit in LOTR. If you enjoy Leadership Swarm decks in MC, you need to try either a Dwarf Swarm or an Outlands deck in LOTR.

Attachments

While Captain America’s shield belongs in his kit, a player who includes at least one leadership hero can have up to three copies of this core set attachment in a player deck. However, due to the unique symbol, only one can be in play at any given time.

Attachments stipulate to whom they can be attached (in this example, only a hero). Note this one also has the unique symbol, so there can only be one Steward of Gondor. Even though this powerful attachment belongs to the Leadership sphere (note the purple Leadership hue and rune symbols), it can be played on Tactics Gimli if your other heroes can generate two Leadership resources. Or, in a multiplayer game, another player could give it to Gimli. Unlike MC, you can generally play attachments onto other players’ heroes an allies. Like MC, some attachments are restricted (in both games, characters can only have two restricted attachments).

Events

Although no funny voices are required, Test of Will is almost an auto-include for any decks running Spirit heroes. Later in the game, the developers frequently added “This card cannot be canceled” as a downright nerf of this card.

Like MC, events in LOTR are one-time effects that are played and then discarded. However, the windows to play events in LOTR are a tad bit more complex. This reflects the more complex anatomy of a turn in LOTR (I’ll discuss turns later). With its blue hue and symbols, A Test of Will belongs to the Spirit sphere. It became such an issue for the development of scenarios that perhaps FFG intentionally limited its appearance in MC (although it creeps in through smaller routes, such as Spider-Ham’s event above or the Protection ally Black Widow).

Phases

MC may have benefited from what FFG learned over the years when they created a two phase turn, because the anatomy of a turn in LOTR can be a stumbling block. Here is a brief, somewhat simplistic overview of the seven phases of a round of the game.

- Resource Phase: each player draws a card and adds one resource to each of their heroes (this is like drawing up to your hand in MC)

- Planning Phase: each player may play allies into their own play area, attachments on their hero/allies or other players’ heroes or allies, and events (this is a portion of the player’s turn in MC, but you do not do any actions here but are allowed to play some events)

- Quest Phase: each player exhausts character for questing—this is a bit vague, and its best parallel to MC, scheming and thwarting, is a bit of a stretch, so I’m going to discuss this shortly (see below)

- Travel Phase: the player(s) can decide to travel to an active location (also see below)(no parallel to MC)

- Encounter Phase: each player may engage enemies from the shared area in order to fight them (unlike MC, enemies enter the game from the encounter deck into a shared space called the Staging Area and are not engaged with any player)

- Combat Phase: each player first defends against those enemies engaged with their heroes and then can attack back (enemies usually get the first attack in LOTR, which is generally not the case in MC)

- Refresh Phase: each character (heroes, allies, and enemies) readies, each player raises their threat by one (this will be discussed shortly as well), and the first player token passes to the next player

Winning and Losing

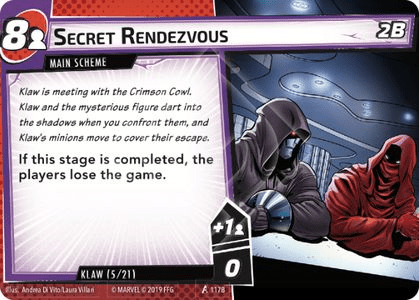

In MC, the goal is usually to defeat two stages of a villain. Most of the scenarios play out this way, and the challenge comes in the various curve balls thrown at you by the encounter deck. You lose if the villain eliminates all the heroes or completes their Main Scheme. In LOTR, it’s inverted: your small group of heroes is trying to place enough progress on the scenario cards to win. You lose if the enemies eliminate your heroes. But there is another loss condition, one placing a time pressure on the game: threat. This word is used in a way that is distinct from its meaning in MC. In LOTR, you have a dial (that looks like your health tracker in MC) that shows your threat. To set up, you combine the threat from your three heroes to determine your starting threat. At the end of each round, you add one. Other game effects will key off your threat level, such as enemies engaging you or certain card abilities. If your total threat ever reaches 50, you lose. While MC adds a tiny amount of something similar with acceleration tokens placed for emptying the encounter deck, you will feel the pressure a lot more in LOTR.

Questing

While perhaps less so than the player cards, the scenario cards of both games share some common anatomy: the usage of A/B sides, the faded art on the A side, the threshold for game state change (in this example, 10 progress for LOTR and 8/player for MC), and italics and bold usage for flavor text and rules respectively.

Remember Gimli’s willpower stat? This value is what heroes and allies can contribute to “questing,” which vaguely means the characters are working together to place “progress” on the main scheme. This is very similar to scheming by villains and minions in MC. You’ll need to exhaust characters (who will then be unavailable for combat), sum their willpower, and compare that to the value of enemy threat (which is different than the hero threat we mentioned above and is an actual stat on the enemy and location cards) on any enemies and locations in Staging. There is a little unknown in this math since after you decide which of your characters will quest, an encounter card is flipped for each player (very analogous to dealing out encounter cards in MC, except here, these cards go to the shared space called the Staging Area and are not engaged with any specific player). If the value of the combined willpower exceeds the value of the combined threat after all cards are revealed, progress has been made! The value of the difference is placed on the active location (which has a threshold allowing it to be “explored” and thereby discarded) and then on the current stage of the Quest card. Beorn’s Path (pictured above) needs 10 progress; once that is reached on this third card of the Passage through Mirkwood quest, you win (if Ungoliant’s Spawn is not in play, as specified at the bottom of that card).

Combat

Speaking of enemies there are several differences between the two games. Enemies attack first, and every foe will receive a Shadow card, which is akin to Boost cards in MC. It would be as if every LOTR enemy had the villainous trait. As you may have inferred, health and healing effects are much more limited in LOTR; health needs to be carefully stewarded. Combat is an intricate puzzle, and in general, you can only interact with enemies engaged with you (LOTR has ranged characters, though, but this is a different “ranged” than in MC; in LOTR, it means only ranged characters can attack another player’s engaged enemies). The only activation that enemies have is attacking (there is no equivalent for scheming).

Modularity

There is less ability to create your own encounters in LOTR than in MC. Scenarios come with rules that stipulate exactly which cards to include. The encounter sets often link up thematically and mechanically; this contributes to their inability to be mixed and matched as in MC. There are no equivalents to Standard or Expert module sets.

Difficulty

LOTR is more challenging than MC. Get ready to lose. Even as you gain experience and move to other quests in other cycles, new challenges will arrive. This may be challenged by others, but I would argue that standard LOTR plays more like an expert or heroic level of MC. While I hate losing, I enjoy the process of discovering where my deck failed and adjusting it.

Although some of the decks I use can handle many quests, there are often quest mechanics that require specific answers; this plays a big factor in the decisions about selecting cards to include. So, while in MC, any deck can attempt any scenario, that is not always the case in LOTR. In addition, it is not just the specific encounter cards that need to be addressed; the wide variety in the structure of each scenario contributes to this.

Variety

The scenarios are much more varied in LOTR: it’s not always about defeating the villain, although there is some of that. There are quests about escorting other characters through dangerous lands, defending locations, rescuing prisoners in dungeons, racing bad guys, solving murders, escaping swamps, battling pirate ships, exploring lost islands, climbing volcanoes, finding Gollum, destroying jewelry, and—a huge crowd favorite—healing an eagle. Even with the same set of heroes, you may need to overhaul a deck to find success with such varied goals and mechanisms. In addition, FFG created a series of “saga expansions” that include six quests for each of Tolkien’s four major novels (The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy). These were the first to offer campaign modes, and later, they retrofitted campaigns to other cycles. These campaigns are similar in complexity to the campaign modes of the MC campaigns for the five scenarios in each deluxe expansion.

If you like MC’s Hela or Kang villains and their mechanisms, you are appreciating a fair amount of LOTR influence. Those scenarios owe a great deal to LOTR. In general, that kind of uniqueness is standard in the various LOTR quests.

FFG Packaging Models

MC’s model of stand-alone hero packs allows players to pick and choose who they want. In addition, having solid player decks does not require extensive collections. LOTR is a wee bit different. The game was originally offered with cycles divided into one three-scenario box and six Adventure Packs with one hero, about five or six copies of player cards in triplicate, and one scenario. These two were about the size of a deluxe expansion and hero pack, respectively. It is important to note that cards designed together were then spread over these boxes and six smaller packs. While some buyers did not purchase entire cycles, deck-building could be tricky since the acquisition was more piecemeal. Taking a cue from MC and Arkham Horror, FFG has repackaged a good deal (but not all) of the LOTR material in a better format. Now, you can pick up an entire cycle’s cards in one box.

This new system is the called the Revised Version, and much of the game has been re-organized for this. Some of the rougher, clunkier or frustrating quests did not make the cut.

Community

Both games have vibrant communities, and that may be one of the best parts about playing these co-operative games. Many players share their knowledge and experience across various formats. Websites such as this one are invaluable. One other website of note would be the Hall of Beorn, which has a series of articles called Beorn’s Path that taught me (and many others!) how to construct decks when I started playing over ten years ago. There is one long-standing podcast (Cardboard of the Rings) and several newer ones (such as Late of the Rings, that began with the Revised core and caters especially to players newer to the game). There are also many YouTube channels as people play the game. For whatever reason, MC websites have not had the staying power of those dedicated to LOTR (or I haven’t found them yet—educate me if you know better!). Finally, DragnCards is a phenomenal online way to play the game. I have heard rumors of a Marvel mod for the platform, but I have not yet seen it.

Where To Start

The Core Set for LOTR has some similarities to MC in that there are three scenarios included and player cards for all four spheres. There are twelve heroes, three from each sphere. This allows for many combinations, although not all will work well. I think the cores box for MC is a better introduction, as five heroes that can be played in four aspects give you twenty viable options.

While both boxes have three scenarios (perhaps FFG put three villains in the core box as a nod to the three quests that come in the LOTR core set?), the three LOTR scenarios are static in that they do not have modules that can be substituted to adjust the difficulty. Their challenge levels deviate more from each other than the MC villains, with the first being one the easiest quests ever released for the game and the third being one of the hardest ever made (although mitigated a bit with the Revised Core Set campaign cards).

New players will want to consider two other purchases. First, The Dark of Mirkwood pack includes two entertaining scenarios and complements the three quests of the core set well. Together, a new player would have five scenarios of varying difficulty with a solid range of mechanics.

Secondly, FFG took many of the player cards that were not going to be repackaged in their new Revised packaging format and placed them in four Starter Decks: one for dwarves, one for elves, one for the Riders of Rohan, and one for the men of Gondor. Each includes a deck of three heroes and fifty player cards, as well as a bench of a fourth hero and more player cards that can be used in deck-building. Each of these four starter decks approaches the game differently and demonstrates the divergent approaches that players can use for any given quest. I suggest you start with the one that seems most interesting to you.

Together, while admittedly an expensive proposition, buying one Starter Deck and the Dark of Mirkwood would give anyone a great introduction to the game. You would also have enough cards to build some creative decks of your own.

Conclusion

I hope Marvel players will give LOTR a chance. Many elements of MC will carry over and facilitate learning this fine game. For players who love challenges, are enthralled with deck-building, or want to join a great fellowship of players worldwide, LOTR is the one game to rule them all!

Thanks again to Doc_H for writing this article. I’ll be looking for someone to perhaps do a similar article comparing Arkham Horror to LOTR LCG, as those two LCGs borrowed a lot from each other over the years. If you are interested, feel free to reach out. Unfortunately, I do not have enough experiences with Arkham (or Marvel for that matter) to write these articles myself, so it’s great seeing more community members stepping up to write for the blog.

Great article! I would add one thing in favour of LotR – the sense of cooperation and agency. There are MUCH more opportunities for cooperative play and as a player you can act and help others across the whole round, in each phase. When I played Marvel for the first time it struck me as much less cooperative in feel.

LikeLike